How Beethoven’s symphonis changed the world

Philip Clark

Tuesday, March 23, 2021

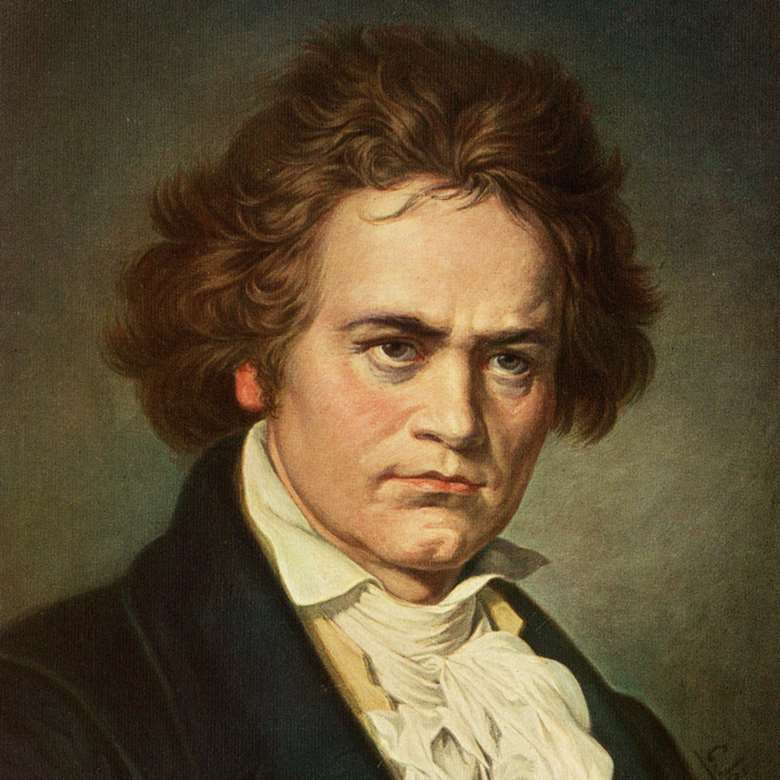

Ludwig van Beethoven's symphonies have influenced every generation of composers since they were written. Riccardo Chailly talks to Philip Clark about the enduring power of the symphonies

Ludwig van Beethoven, the composer who, more than any other, changed music, the sound of music and what it is that composers do, wrote nine symphonies that jolted music out of itself. Life could never – would never – be the same again. The “classical” rationality of structure, harmony, form, melodic development and orchestration span into open-ended possibility. And, nearly 200 years after his death, no one expects the pieces to settle down again any time soon.

As I suggest Chailly’s thoughts about Schumann upset the perceived wisdom of a Beethoven-Brahms-Schoenberg historical lineage, he slides a book off his shelf about the relationship of later composers to the Choral Symphony. Documenting Mahler’s retouching of the Ninth’s orchestration, the book also includes a section devoted to Schoenberg, and I see first-hand his analysis of the fifth movement’s opening bars and his additional brass parts. “Schoenberg absolutely understood the core message of Beethoven’s music, but you’re right, it’s forgotten how strong Schoenberg’s interest in his music was. The link between Brahms and Schoenberg is audible but you don’t hear direct traces of Beethoven in Schoenberg. But, looking at this, I see how analytical was his understanding of Beethoven. I hear very close links between Brahms and Mendelssohn in their perfection of form. But Beethoven and Schumann were both barrier-breakers in terms of form, in their limitless wish to expand the barriers of tonality.” Given that Stravinsky’s credo was to expand tonality’s barriers without, until the last years of his life, trashing them altogether, his naked antipathy towards Beethoven was one of his characteristic foibles, although nothing compared with Cage’s downright hostility. Eric Walter White, Stravinsky’s biographer, thought his attitude was “of a creator and not a critic”; Cage rained on long-cherished ideas about Beethoven with parades of benevolent ridicule suggesting that his music was no longer “useful” creatively, sounding, as it did, like “movie music, constantly changing its emotional suggestions”. Apropos Stravinsky and Beethoven, Chailly thinks that programming their work together is, paradoxically, always successful because of their sharp attack and the “uncompromising character of both styles”. And Cage? “That’s very Cage what you say! But I disagree in the sense that Beethoven, as a logical builder of harmonies, is so advanced compared with even half a century earlier, that it remains alarmingly new. And we must not forget that Cage wanted to provoke extreme reactions.”

To love music can be to hate music, and that’s fine. Stravinsky and Cage needed Beethoven – who drove the idea of functional, arrow-headed directional harmony beyond the sublime – as a conflict to be worked through as they found their art: Stravinsky’s neo-classicism, Cage’s so-called anarchic harmony, where sounds were allowed autonomy from narrative targets and the need to obey an internally consistent grammar. Great composers do more than refresh music; they create new contexts for harmony. Beethoven created his, Stravinsky and Cage theirs.

As our conversation turns to the narrative content of Beethoven’s symphonies, Chailly cites the slow movements of theEroica, Pastoral and Choral symphonies as moments that changed music for good. He talks about the “triumph of the horizontal shape of the score” (as opposed to vertical harmony) and about “the endless shape of the narrative from the first to last bar.” A paradox of the Fifth Symphony is, I suggest, that the directness of its emotional impact is counterpointed against its labyrinthine narrative structure: material plunges through trapdoors, new windows are there all of a sudden, like internet pop-ups, the narrative direction is no longer solidly A to B.This reminds me that, for Mahler, Beethoven was the master,” Chailly responds. “If you compare any of those slow movements I mentioned to the Andante of Mahler’s Sixth, you can hear how Mahler develops the idea of the so-called ‘endless melody’. Mahler is entranced by Beethoven’s endless fantasy. Think for a moment of all the beginnings of Mahler’s symphonies – and I include the 10th and Das Lied von der Erde in that; just think about, say, the first four bars and how Mahler never copied himself. Even when he used a funeral march to spark his creativity, it was never the same. Now do the same thing for Beethoven’s nine symphonies and notice how each one is different; how in the Eroica and Fifth, there is no need for an introduction; how in the Fourth Beethoven has this long, elaborate introduction.

“Hypothetically, my ideal would be to play the nine symphonies non-stop. I have analysed the end of one symphony and the start of the next, and then you see a certain logic emerge; one symphony follows the previous one with a different tonality, shape and character. But all the symphonies belong to this unity of one oeuvre, one opus. Mahler learnt to do the same from Beethoven.”

Having chased Beethoven’s legacy towards the Cageian brink, Chailly’s words remind me again of another composer with which he is strongly associated: Edgard Varèse. Like Beethoven’s symphonies, Varèse’s major orchestral works –Amériques, Arcana, Déserts – are a unified oeuvre defined by how alike and unlike they are: as alike and unlike as trees. Like Beethoven, Varèse elbowed his way past protocols of traditional form, forms that Beethoven himself established. But I have a vision of Beethoven looking down on Varèse, understanding entirely why he had to destroy to create, and cheerfully waving him on his way. Chailly’s three Barbican concerts take place in October and November, shortly after the release of his cycle. To reinforce the idea of Beethoven as a timeless source of ideas, he has commissioned Colin Matthews, Bruno Mantovani, Steffen Schleiermacher, Friedrich Cerha and Carlo Boccadoro to provide new related satellite works. And I wonder if Beethoven’s greatest legacy – a more profound lesson than developing the style and idiom of his notes – was that he called “open sesame”, giving composers permission to question the assumed parameters of music. What is music? Why music? How music? Questions only fools would ignore.

Influenced by The Nine...

Schubert Symphony No 9, D944 (1826)

Completed the year before Beethoven’s death, Schubert’s Great C major Symphony was, to square this circle of influences, thought by Schumann to be the greatest symphony since Beethoven’s nine. Early in his career, Schubert doubted “anyone can do anything after Beethoven” and hesitatingly dedicated his Variations on a French Song, D624, to him, a puzzle because the piece had only minimal surface similarity to Beethoven. But Schubert was scooping his own compositional identity from Beethoven. The Ninth, written five years later, finds him grappling with what it means to write a symphony. Schubert’s resplendent horn introduction lays it on the line, and a surreal harmonic fissure in the finale makes it feel like the music is leaping 100 years into the future.

Recommended recording Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra / Nikolaus Harnoncourt (Warner Classics) Read review

Schumann Fantasie in C major, Op 17 (1836)

A monument to Beethoven – literally. The roots of Schumann’s Fantasie date back to 1836, when Schumann composed a piano work to help lobby for funds to build a statue dedicated to Beethoven in Bonn, his home town.

Allusions to Beethoven are embossed into its fabric: a quote from Beethoven’s song-cycle An die ferne Geliebte was slipped into the coda of the first movement seemingly without anybody noticing at the time; the message secreted inside the words, “Accept these songs, beloved, which I sang for you alone”, was a subliminal one directed at Clara.

Originally, the finale was going to riff on Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony but Schumann had second thoughts; nevertheless, ghostly traces of Beethoven’s slow movement remain in the bass though.

Recommended recording Maurizio Pollini (DG) Read review

Brahms Symphony No 1 (1876)

After its two-decade gestation, is Brahms’s Symphony No 1 really, as the conductor Hans von Bülow famously described it, “Beethoven’s Tenth”? Well, von Bülow was one of Brahms’s most enthusiastic supporters but he’s right only in the sense that Beethoven’s First is “Haydn 105” or “Mozart 42”.

Beethoven was the undeniable stylistic spur: the symphony’s four-movement construct, including its “listen up” prologue, is a chip off the Beethovenian block; the melodic contours of Brahms’s finale seem traced over the equivalent moment in Beethoven’s Ninth and the persistent “der der der DA” rhythmic rap is hardly unfamiliar. Yet those same melodic contours, the harmonic conflict birthed in the opening, the sound of the orchestration, could only be Brahms. Beethoven has been entirely distilled.

Recommended recording ORR / Sir John Eliot Gardiner (SDG) Read review

Ives Concord Sonata (1915)

Ives’s Concord Sonata is a meditation on “the spirit of transcendentalism associated in the minds of many with Concord, Massachusetts”, a reference to such philosophers as Emerson and Thoreau. But among a trademark Ivesian collage of American folk tunes, hymns and marches, the opening bars of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony are obsessively recalled and re-contextualised.

To Ives, Beethoven’s music transcended our understanding of what music could be; the opening of Beethoven’s Fifth, the most recognisable hook in all classical music, is “dematerialised” by Ives into an open-ended question mark. The addition of obbligato flute and viola parts – in a piano sonata! – implies the format itself must be transcended. And Beethoven is the key.

Recommended recording Varied Air: Charles Ives Piano Music Philip Mead (Metier)

Mauricio Kagel Ludwig van (1970)

Ludwig van exists as both film and spin-off instrumental work. Mauricio Kagel’s original film was a backhanded tribute for the 1970 Beethoven bicentenary, where Beethoven himself arrives at Bonn Station to see how the culture industry is treating his memory.

The most famous scene is shot in Beethoven’s music room: the camera pans slowly around the room where every surface is pasted in fragments of Beethoven scores. As the camera moves, an ensemble plays these scraps haphazardly, and we hear Beethoven with the syntax removed; familiar phrases trip over one another, gestures are remade as fresh sources of sound. Kagel made a concert version of the music room scene, but his original film remains provocative and refreshing.

How Beethoven’s symphonis changed the world

Philip Clark

Tuesday, March 23, 2021

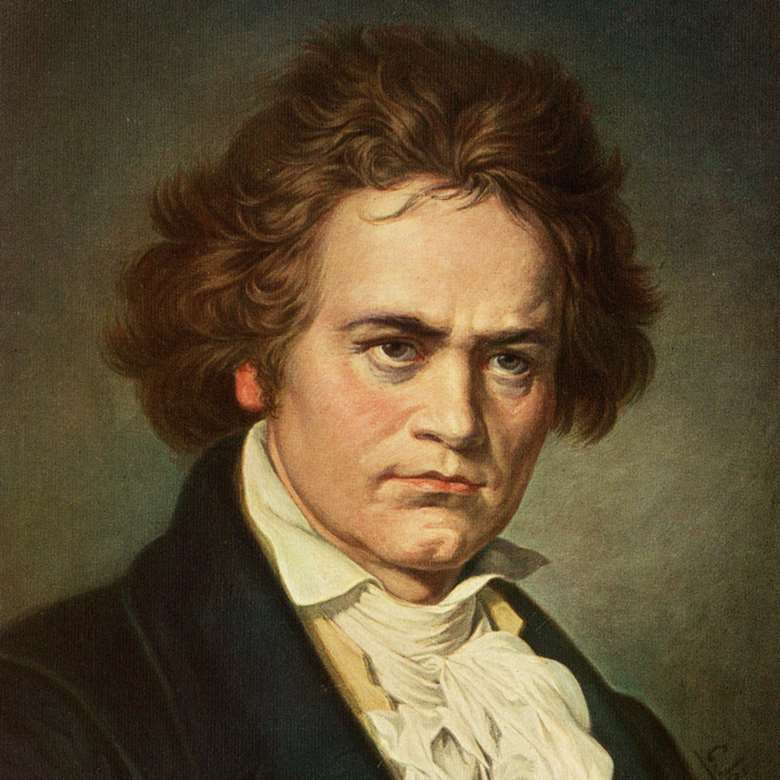

Ludwig van Beethoven's symphonies have influenced every generation of composers since they were written. Riccardo Chailly talks to Philip Clark about the enduring power of the symphonies

Ludwig van Beethoven, the composer who, more than any other, changed music, the sound of music and what it is that composers do, wrote nine symphonies that jolted music out of itself. Life could never – would never – be the same again. The “classical” rationality of structure, harmony, form, melodic development and orchestration span into open-ended possibility. And, nearly 200 years after his death, no one expects the pieces to settle down again any time soon.

As I suggest Chailly’s thoughts about Schumann upset the perceived wisdom of a Beethoven-Brahms-Schoenberg historical lineage, he slides a book off his shelf about the relationship of later composers to the Choral Symphony. Documenting Mahler’s retouching of the Ninth’s orchestration, the book also includes a section devoted to Schoenberg, and I see first-hand his analysis of the fifth movement’s opening bars and his additional brass parts. “Schoenberg absolutely understood the core message of Beethoven’s music, but you’re right, it’s forgotten how strong Schoenberg’s interest in his music was. The link between Brahms and Schoenberg is audible but you don’t hear direct traces of Beethoven in Schoenberg. But, looking at this, I see how analytical was his understanding of Beethoven. I hear very close links between Brahms and Mendelssohn in their perfection of form. But Beethoven and Schumann were both barrier-breakers in terms of form, in their limitless wish to expand the barriers of tonality.” Given that Stravinsky’s credo was to expand tonality’s barriers without, until the last years of his life, trashing them altogether, his naked antipathy towards Beethoven was one of his characteristic foibles, although nothing compared with Cage’s downright hostility. Eric Walter White, Stravinsky’s biographer, thought his attitude was “of a creator and not a critic”; Cage rained on long-cherished ideas about Beethoven with parades of benevolent ridicule suggesting that his music was no longer “useful” creatively, sounding, as it did, like “movie music, constantly changing its emotional suggestions”. Apropos Stravinsky and Beethoven, Chailly thinks that programming their work together is, paradoxically, always successful because of their sharp attack and the “uncompromising character of both styles”. And Cage? “That’s very Cage what you say! But I disagree in the sense that Beethoven, as a logical builder of harmonies, is so advanced compared with even half a century earlier, that it remains alarmingly new. And we must not forget that Cage wanted to provoke extreme reactions.”

To love music can be to hate music, and that’s fine. Stravinsky and Cage needed Beethoven – who drove the idea of functional, arrow-headed directional harmony beyond the sublime – as a conflict to be worked through as they found their art: Stravinsky’s neo-classicism, Cage’s so-called anarchic harmony, where sounds were allowed autonomy from narrative targets and the need to obey an internally consistent grammar. Great composers do more than refresh music; they create new contexts for harmony. Beethoven created his, Stravinsky and Cage theirs.

As our conversation turns to the narrative content of Beethoven’s symphonies, Chailly cites the slow movements of theEroica, Pastoral and Choral symphonies as moments that changed music for good. He talks about the “triumph of the horizontal shape of the score” (as opposed to vertical harmony) and about “the endless shape of the narrative from the first to last bar.” A paradox of the Fifth Symphony is, I suggest, that the directness of its emotional impact is counterpointed against its labyrinthine narrative structure: material plunges through trapdoors, new windows are there all of a sudden, like internet pop-ups, the narrative direction is no longer solidly A to B.This reminds me that, for Mahler, Beethoven was the master,” Chailly responds. “If you compare any of those slow movements I mentioned to the Andante of Mahler’s Sixth, you can hear how Mahler develops the idea of the so-called ‘endless melody’. Mahler is entranced by Beethoven’s endless fantasy. Think for a moment of all the beginnings of Mahler’s symphonies – and I include the 10th and Das Lied von der Erde in that; just think about, say, the first four bars and how Mahler never copied himself. Even when he used a funeral march to spark his creativity, it was never the same. Now do the same thing for Beethoven’s nine symphonies and notice how each one is different; how in the Eroica and Fifth, there is no need for an introduction; how in the Fourth Beethoven has this long, elaborate introduction.

“Hypothetically, my ideal would be to play the nine symphonies non-stop. I have analysed the end of one symphony and the start of the next, and then you see a certain logic emerge; one symphony follows the previous one with a different tonality, shape and character. But all the symphonies belong to this unity of one oeuvre, one opus. Mahler learnt to do the same from Beethoven.”

Having chased Beethoven’s legacy towards the Cageian brink, Chailly’s words remind me again of another composer with which he is strongly associated: Edgard Varèse. Like Beethoven’s symphonies, Varèse’s major orchestral works –Amériques, Arcana, Déserts – are a unified oeuvre defined by how alike and unlike they are: as alike and unlike as trees. Like Beethoven, Varèse elbowed his way past protocols of traditional form, forms that Beethoven himself established. But I have a vision of Beethoven looking down on Varèse, understanding entirely why he had to destroy to create, and cheerfully waving him on his way. Chailly’s three Barbican concerts take place in October and November, shortly after the release of his cycle. To reinforce the idea of Beethoven as a timeless source of ideas, he has commissioned Colin Matthews, Bruno Mantovani, Steffen Schleiermacher, Friedrich Cerha and Carlo Boccadoro to provide new related satellite works. And I wonder if Beethoven’s greatest legacy – a more profound lesson than developing the style and idiom of his notes – was that he called “open sesame”, giving composers permission to question the assumed parameters of music. What is music? Why music? How music? Questions only fools would ignore.

Influenced by The Nine...

Schubert Symphony No 9, D944 (1826)

Completed the year before Beethoven’s death, Schubert’s Great C major Symphony was, to square this circle of influences, thought by Schumann to be the greatest symphony since Beethoven’s nine. Early in his career, Schubert doubted “anyone can do anything after Beethoven” and hesitatingly dedicated his Variations on a French Song, D624, to him, a puzzle because the piece had only minimal surface similarity to Beethoven. But Schubert was scooping his own compositional identity from Beethoven. The Ninth, written five years later, finds him grappling with what it means to write a symphony. Schubert’s resplendent horn introduction lays it on the line, and a surreal harmonic fissure in the finale makes it feel like the music is leaping 100 years into the future.

Recommended recording Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra / Nikolaus Harnoncourt (Warner Classics) Read review

Schumann Fantasie in C major, Op 17 (1836)

A monument to Beethoven – literally. The roots of Schumann’s Fantasie date back to 1836, when Schumann composed a piano work to help lobby for funds to build a statue dedicated to Beethoven in Bonn, his home town.

Allusions to Beethoven are embossed into its fabric: a quote from Beethoven’s song-cycle An die ferne Geliebte was slipped into the coda of the first movement seemingly without anybody noticing at the time; the message secreted inside the words, “Accept these songs, beloved, which I sang for you alone”, was a subliminal one directed at Clara.

Originally, the finale was going to riff on Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony but Schumann had second thoughts; nevertheless, ghostly traces of Beethoven’s slow movement remain in the bass though.

Recommended recording Maurizio Pollini (DG) Read review

Brahms Symphony No 1 (1876)

After its two-decade gestation, is Brahms’s Symphony No 1 really, as the conductor Hans von Bülow famously described it, “Beethoven’s Tenth”? Well, von Bülow was one of Brahms’s most enthusiastic supporters but he’s right only in the sense that Beethoven’s First is “Haydn 105” or “Mozart 42”.

Beethoven was the undeniable stylistic spur: the symphony’s four-movement construct, including its “listen up” prologue, is a chip off the Beethovenian block; the melodic contours of Brahms’s finale seem traced over the equivalent moment in Beethoven’s Ninth and the persistent “der der der DA” rhythmic rap is hardly unfamiliar. Yet those same melodic contours, the harmonic conflict birthed in the opening, the sound of the orchestration, could only be Brahms. Beethoven has been entirely distilled.

Recommended recording ORR / Sir John Eliot Gardiner (SDG) Read review

Ives Concord Sonata (1915)

Ives’s Concord Sonata is a meditation on “the spirit of transcendentalism associated in the minds of many with Concord, Massachusetts”, a reference to such philosophers as Emerson and Thoreau. But among a trademark Ivesian collage of American folk tunes, hymns and marches, the opening bars of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony are obsessively recalled and re-contextualised.

To Ives, Beethoven’s music transcended our understanding of what music could be; the opening of Beethoven’s Fifth, the most recognisable hook in all classical music, is “dematerialised” by Ives into an open-ended question mark. The addition of obbligato flute and viola parts – in a piano sonata! – implies the format itself must be transcended. And Beethoven is the key.

Recommended recording Varied Air: Charles Ives Piano Music Philip Mead (Metier)

Mauricio Kagel Ludwig van (1970)

Ludwig van exists as both film and spin-off instrumental work. Mauricio Kagel’s original film was a backhanded tribute for the 1970 Beethoven bicentenary, where Beethoven himself arrives at Bonn Station to see how the culture industry is treating his memory.

The most famous scene is shot in Beethoven’s music room: the camera pans slowly around the room where every surface is pasted in fragments of Beethoven scores. As the camera moves, an ensemble plays these scraps haphazardly, and we hear Beethoven with the syntax removed; familiar phrases trip over one another, gestures are remade as fresh sources of sound. Kagel made a concert version of the music room scene, but his original film remains provocative and refreshing.

تعليق