توقف التعريض الضوئي في التصوير الفوتوغرافي – دليل المبتدئين

Exposure Stops in Photography – A Beginner’s Guide

هناك الكثير من الازدواجية في التصوير الفوتوغرافي. من ناحية، إنه الضوء والموضوع، إنه القصة التي نرويها والقصة التي يراها المشاهد، إنه شعور، عاطفة، حالة، رمز، استعارة. يبدو شاعريا، أليس كذلك؟ ومن ناحية أخرى، فهو علم خالص، كل جزء منه - بدءًا من الضوء المذكور الذي ينتقل عبر تصميم عدسة معقد، وصولاً إلى المشهد الذي يتم طبعه سواء على قطعة من فيلم حساس للضوء أو، مؤقتًا، على جهاز رقمي. المستشعر. وهذا الجزء العلمي من التصوير الفوتوغرافي يجلب معه جميع أنواع المصطلحات، وهي مصطلحات قد لا تكون ضرورية للعملية الإبداعية، ولكن فيما يتعلق بالتنفيذ الماهر، لا يمكنك الاستغناء عن فهمها لفترة طويلة جدًا. يحتاج الرسام إلى معرفة فرشه في مرحلة ما، أليس كذلك؟

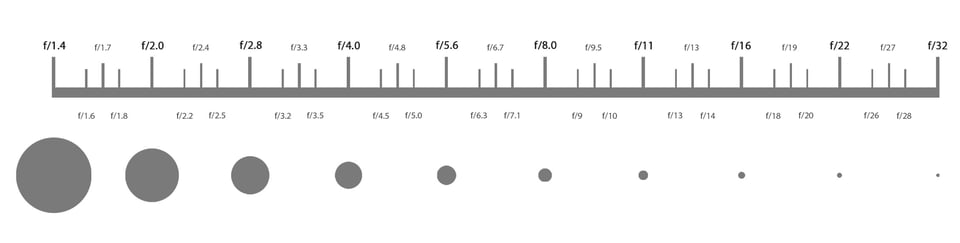

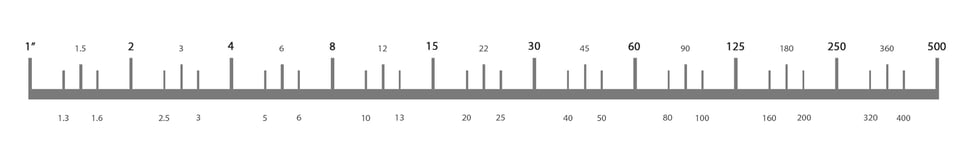

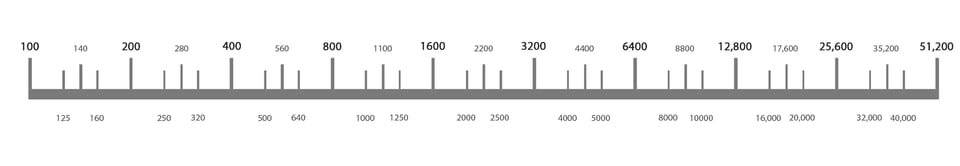

وهكذا عدنا إلى تغطية الأساسيات، وهو أمر لا بد أنك لاحظته بالتأكيد. في هذه المقالة، سأتحدث عن مصطلح آخر مربك عند اللقاء الأول يستخدم في التصوير الفوتوغرافي، وبشكل أكثر تحديدًا – توقف التعرض. سأحاول شرح ماهيتها وكيفية ارتباط توقفات معلمات مثلث التعريض المختلفة - سرعة الغالق وفتحة العدسة وحساسية ISO - بالإضافة إلى إعطائك أمثلة لما يعتبر قيم توقف عادية لكل معلمة، وما هي القيم الكاملة ونصف وثالث توقف.

There is so much duality in photography. On one hand, it’s the light and the subject, it’s the story we tell and the story the viewer sees, it’s a feeling, an emotion, a state, a symbol, a metaphor. Sounds poetic, doesn’t it? On the other hand, it’s pure science, every single bit of it – from the said light traveling through a complex lens design, all the way to the scene being imprinted whether on a piece of light-sensitive film or, temporarily, on a digital sensor. And that scientific part of photography brings all sorts of terms with it, terms that may not be necessary for the creative process, but as far as skillful execution goes, you can’t do without understanding them for very long. A painter needs to know his brushes at some point, right?

And so we are back to covering basics, something you surely must have noticed. In this article, I will talk about yet another, confusing-at-first-encounter term used in photography, more specifically – exposure stops. I will try to explain what they are and how stops of different exposure triangle parameters – shutter speed, aperture and ISO sensitivity – correlate, as well as give you examples of what are considered to be regular stop values of each parameter, and what are full, half and third-stops.

Exposure Stops in Photography – A Beginner’s Guide

هناك الكثير من الازدواجية في التصوير الفوتوغرافي. من ناحية، إنه الضوء والموضوع، إنه القصة التي نرويها والقصة التي يراها المشاهد، إنه شعور، عاطفة، حالة، رمز، استعارة. يبدو شاعريا، أليس كذلك؟ ومن ناحية أخرى، فهو علم خالص، كل جزء منه - بدءًا من الضوء المذكور الذي ينتقل عبر تصميم عدسة معقد، وصولاً إلى المشهد الذي يتم طبعه سواء على قطعة من فيلم حساس للضوء أو، مؤقتًا، على جهاز رقمي. المستشعر. وهذا الجزء العلمي من التصوير الفوتوغرافي يجلب معه جميع أنواع المصطلحات، وهي مصطلحات قد لا تكون ضرورية للعملية الإبداعية، ولكن فيما يتعلق بالتنفيذ الماهر، لا يمكنك الاستغناء عن فهمها لفترة طويلة جدًا. يحتاج الرسام إلى معرفة فرشه في مرحلة ما، أليس كذلك؟

وهكذا عدنا إلى تغطية الأساسيات، وهو أمر لا بد أنك لاحظته بالتأكيد. في هذه المقالة، سأتحدث عن مصطلح آخر مربك عند اللقاء الأول يستخدم في التصوير الفوتوغرافي، وبشكل أكثر تحديدًا – توقف التعرض. سأحاول شرح ماهيتها وكيفية ارتباط توقفات معلمات مثلث التعريض المختلفة - سرعة الغالق وفتحة العدسة وحساسية ISO - بالإضافة إلى إعطائك أمثلة لما يعتبر قيم توقف عادية لكل معلمة، وما هي القيم الكاملة ونصف وثالث توقف.

There is so much duality in photography. On one hand, it’s the light and the subject, it’s the story we tell and the story the viewer sees, it’s a feeling, an emotion, a state, a symbol, a metaphor. Sounds poetic, doesn’t it? On the other hand, it’s pure science, every single bit of it – from the said light traveling through a complex lens design, all the way to the scene being imprinted whether on a piece of light-sensitive film or, temporarily, on a digital sensor. And that scientific part of photography brings all sorts of terms with it, terms that may not be necessary for the creative process, but as far as skillful execution goes, you can’t do without understanding them for very long. A painter needs to know his brushes at some point, right?

And so we are back to covering basics, something you surely must have noticed. In this article, I will talk about yet another, confusing-at-first-encounter term used in photography, more specifically – exposure stops. I will try to explain what they are and how stops of different exposure triangle parameters – shutter speed, aperture and ISO sensitivity – correlate, as well as give you examples of what are considered to be regular stop values of each parameter, and what are full, half and third-stops.

تعليق